The Ottoman Empire, based in Turkey, became the dominant power in most of the Middle East in the 1500s. They eventually extended their rule into North Africa, Eastern Europe, and south of Turkey into the ancient lands known as the Holy Land, the Levant, and many other names. Historically home to many peoples, they were then predominantly populated by Arabs. Divided into provinces under the Ottomans, they would eventually become the modern countries of Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Kuwait, Palestine, and Israel.

The Ottoman Empire was long a rival to the Christian Kingdoms of Europe, but as time went on the geopolitical situation became more complicated, as they usually do. While ostensibly enemies, delegations of the British, French, Ottoman, and other empires could be found collaborating on colonial projects. Ultimately, this status quo was toppled when the Ottoman Empire allied with Germany in World War 1.

After the defeat of the Central Powers, the Ottoman Empire was divided among the Allies. France took control of what would become Syria and Lebanon. Britain oversaw what would become Palestine, Jordan and Iraq. Britain made 3 contradicting arrangements leading up to this outcome that set many of the region’s modern conflicts in motion.

In 1915, while WW1 was still being fought, the British government made a deal with Sharif Husayn, the Ottoman governor of Hijaz, a region in modern-day Saudi Arabia that encompassed Mecca and Medina. The deal stipulated that Husayn’s forces, mostly Arab, would revolt against the Turks in Arabia and Syria in exchange for Britain creating an independent Arab state from the Ottoman territory. Britain’s efforts on this operation were overseen by Colonel T.E. Lawrence (AKA Lawrence of Arabia).

In 1916, while the Arab revolts began, Britain signed the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement with France to divide up the former Ottoman lands between themselves as a collection of mandates with borders based on their own colonial interests, rather than those of their Arab allies.

The third British agreement that represented a clear conflict of interest was the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

Zionism began in earnest in the 1880s as waves of Jewish immigration to a part of Jerusalem known historically as Zion. It was fueled largely by violent lynchings (pogroms) of Jewish people throughout Europe. Due to this violence many Jews became convinced of the necessity of an independent Jewish state. Hungarian-Jewish journalist Theodor Herzl wrote extensively on the topic and helped found the World Zionist Organization. British Zionists were instrumental in pressuring the authorities in the Palestinian Mandate to support their nationalist goals. The resulting Balfour Declaration read as follows:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

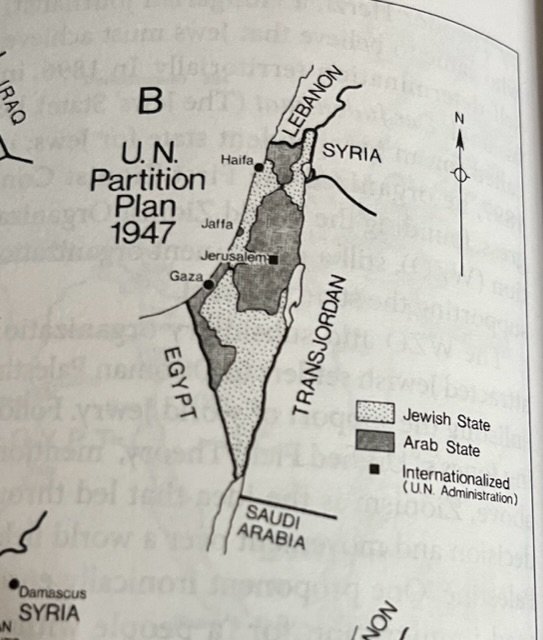

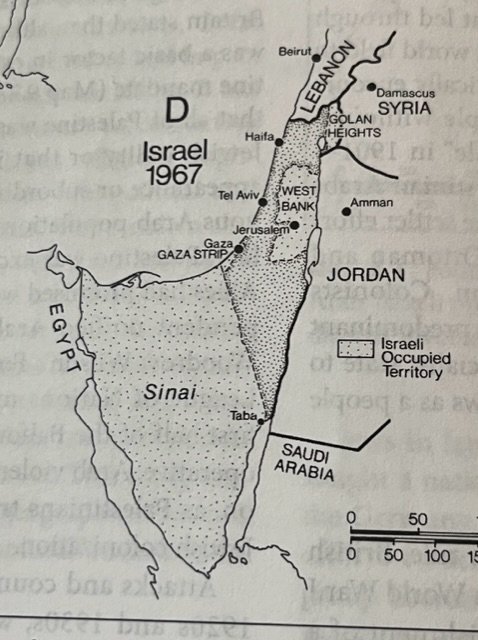

There are diverse opinions about why this particular goal was really adopted by the British government. As it sought to optimize its control over the Palestinian Mandate and balance it with its numerous other colonial interests around the world, commitments to Jewish and Arab populations waxed and waned. Unsurprisingly, violence and struggles over land and resources intensified between Palestinians and Jews. Jewish immigration increased, Arab opposition to Jews who had lived in Palestine for generations hardened, and both sides lashed out at British colonial authorities. Britain would eventually relinquish its responsibility for Palestine to the newly created United Nations in 1947.

Zionism was not created as a genocidal movement, though many Zionists have embraced genocidal tactics and aims. Arab nationalism is not fundamentally anti-Israel, though numerous Arab nationalists have used Israel as an enemy to build political bases, while doing little to protect Palestinians from Israel’s right wing. Many European colonizers worked to improve the lives of the people their governments had conquered, yet colonialism and the cynical race for wealth that fuels it could not be restrained by good intentions or isolated acts of benevolence. A violent system invariably breeds more violence.

Source:

“The Arab-Israeli Problem.” Middle East Patterns, 6th ed. p252-264. 2014. Colbert C. Held, John Thomas Cummings. Westview Press.

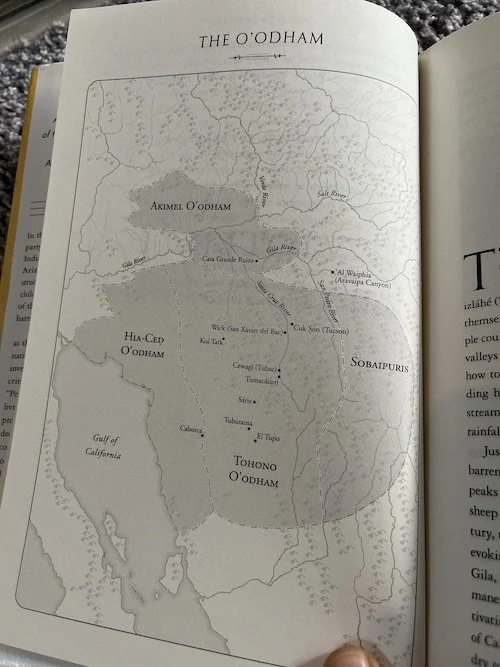

Map. “Territorial evolution of Israel, from Palestinian mandate to contemporary state, with occupied territories (part A)” John V. Cotter