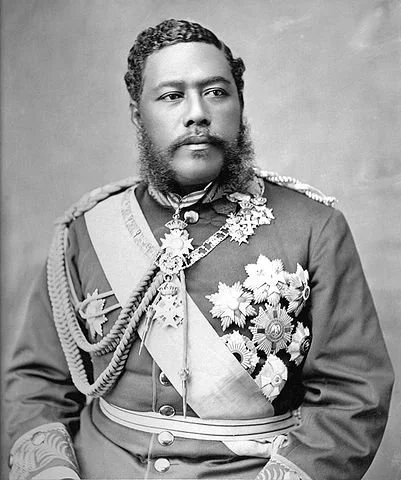

Portrait of King Kalākaua. James J. Williams. Circa 1882. Public Domain.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kingdavidkalakaua_dust.jpg

King David Kalākaua’s reign began in 1874 with a bitter election and accusations of corruption. His opponent Emma Rooke, the widow of Kamehameha IV, retained significant popular support among many indigenous Hawaiians. On the other end of the political spectrum, he was under intense pressure, like his predecessors, to facilitate the priorities of wealthy plantation owners whose ultimate goal was US annexation.

Most Hawaiians favored allying the kingdom closer to Britain, another monarchy. However, the US had long made it clear they saw the Hawaiian islands as crucial to US security and would not abide another European power taking possession of the kingdom. The large number of American plantation owners and businessmen working in the Hawaiian government helped bolster this claim. American and European businessmen had already accomplished the political goals of converting the kingdom’s land tenure system to one of private property and passing laws allowing immigrants to purchase land.

The main plantation commodity on the islands was sugar. Hawaiian and American agents attempted to negotiate a reciprocity treaty in 1855 but Louisiana sugar planters blocked this threat to their profits. 7 years later Southern planters were at war with the United States and Hawaiian sugar saw a boom. After the war concluded these profits decreased and talks for a reciprocity treaty renewed.

US generals visited the islands in 1872 to evaluate areas for military use, and found Pearl Harbor a prime location. Hawai’i’s government was initially willing to grant exclusive use of the harbor to the US in exchange for the ability to import sugar to the US free of tariffs, but public outrage forced the government to withdraw the offer.

After his election in 1874, King Kalākaua renewed efforts to secure a reciprocity treaty for Hawai’i’s sugar planters. The US settled for a clause that prevented the kingdom’s government from leasing territory to any foreign power for the life of the treaty. The act was signed in 1875. The subsequent boom in sugar production also dramatically affected the demographics of the kingdom as the planters imported Chinese and Japanese contract laborers in large numbers.

When the agreement came up for renewal in 1885, the US took a firmer position on demanding exclusive access to Pearl Harbor. The agreement had been a boon for the sugar producers, and by extension the royal family that taxed them, but most Hawaiians saw little benefit and many of the indigenous Hawaiians were still adamantly opposed to ceding Pearl Harbor to the Americans or any other foreign power. King Kalākaua resisted adding the clause guaranteeing US naval access to the harbor, heightening tensions between his administration and the planter class.

The treaty did not benefit the US economically, but Hawai’i’s sugar producers stood to lose substantial gains if it was not renewed, causing them to tighten their grip on the Hawaiian government. A group of American businessmen, many descended from missionary families, organized an anti-royalist, pro-US-annexation “Reform Party.” Many of these men were also part of a secret cabal known as the Hawaiian League that planned to hasten annexation by staging a coup.

Lorrin A. Thurston. Approx 1892. Author unknown. Public Domain.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lorrin_A._Thurston,_1892.jpg

Lorrin Thurston, the grandson of missionaries, took the lead in executing an insurrection. He commanded a 300-man militia called the Honolulu Rifles. They were almost exclusively White. On June 30, the Hawaiian League demanded that King Kalākaua dismiss his cabinet, headed by Walter M. Gibson, a White politician who opposed the goals of the Hawaiian League.

The next day the Honolulu Rifles took control of a large shipment of arms from an Australian ship, nearly lynched Gibson, exiling him to San Francisco at the last minute, and proceeded to join the members of the Hawaiian League as they informed the king that they would replace his cabinet with their own members, Thurston among them, and that they were drafting a new constitution that he would be signing into law. The king sought counsel from several American and British ministers not aligned with the League, but none were confident enough to oppose them and advised him to comply with their demands. This document was literally signed at gunpoint, earning it the name, the Bayonet Constitution.

It removed most of the king’s authority by giving the legislature veto powers and stipulating that any official actions required the signature of at least 1 cabinet member. It also changed the voting rights of the kingdom by allowing male citizens and resident aliens of American, European, or Hawaiian descent to vote, provided they could pass a literacy test in a language of those races, and meet the property and income requirements. The literacy and property requirements were features of previous constitutions, but the racial language was used to disenfranchise Chinese and Japanese residents, most of whom were plantation laborers or formerly had been, and at the same time give the vote to Portuguese laborers largely controlled by members of the Reform Party.

The Bayonet Constitution was never ratified by the Hawaiian Legislature, even after the snap election that brought in a largely Hawaiian League government. Later that summer, the king signed the renewal of the reciprocal agreement, with the clause that guaranteed the US exclusive use of Pearl Harbor for the length of the treaty. Kalākaua remained the head of state, but was sidelined politically. The government of the kingdom was taken over by the Hawaiian League, and the United States gained a valuable naval base in the Pacific region. Most indigenous Hawaiians had long suspected American planters and politicians planned on replacing their government and began organizing against it.

Sources:

King David Kalākaua- wbur

The 1887 Bayonet Constitution: Beginning of the Insurgency- Hawaiian Kingdom blog

Lorrin A. Thurston- Encyclopedia Britannica

Robert William Wilcox- Crown of Hawai’i

La Croix, Sumner J., and Christopher Grandy. “The Political Instability of Reciprocal Trade and the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” The Journal of Economic History 57, no. 1 (1997): 161–89.

Moblo, Pennie. “Leprosy, Politics, and the Rise of Hawaii’s Reform Party.” The Journal of Pacific History 34, no. 1 (June 1999): 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223349908572892.

Osorio, Jonathan Kamakawiwo’ole. “‘ What Kine Hawaiian Are You?’: A Mo’olelo about Nationhood, Race, History, and the Contemporary Sovereignty Movement in Hawai’i.” The Contemporary Pacific 13, no. 2 (2001): 359–79.