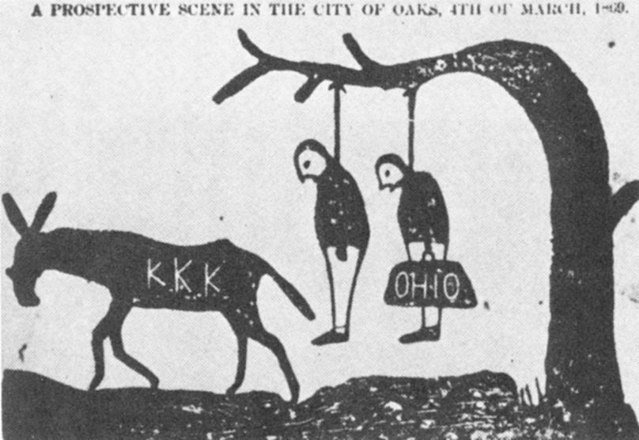

A cartoon threatening that the KKK will lynch scalawags (left) and carpetbaggers (right) on March 4, 1869. Tuscaloosa, Alabama Independent Monitor, Sept. 1, 1868. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kkk-carpetbagger-cartoon.jpg

In the South after the Civil War, the Union’s victory was followed by terrorism.

The Ku Klux Klan was founded in 1865 in Tennessee by Confederate Veterans. It was only one of many secret terrorist groups that formed immediately after the end of the war. While many groups had chapters in different states, none of them exercised much central control. The groups formed and were directed by local members resisting Republican political domination and suppressing the political, social, and economic freedom of newly freed Black people in their towns and cities. The Klan became infamous as “midnight riders,” raiding homes, burning property, and often murdering Black and White people who challenged the old White Supremacist Democratic Party order.

The original klansmen wore hoods and disguises while conducting attacks, but they were not very uniform. The white hoods and burning crosses associated with the KKK were part of the revival movement in the 1910s and 20s.

Mississippi Ku-Klux members in the disguises in which they were captured. Artist Unknown. Harper's Weekly January 27, 1872. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mississippi_ku_klux.jpg

This political violence surged throughout the 1860s, leading to the First and Second Enforcement Acts (1870, 1871), and the Ku Klux Klan Act (1871). These acts authorized the President and Congress to use military powers to enforce the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments (The Reconstruction Amendments) passed between 1865-70. These amendments codified the citizenship and political rights of Black Americans. In reality, US troops were needed to ensure Black voters could participate in elections or hold offices they’d been elected to. Where there was no military presence, vigilantes like the Klan were largely successful in suppressing the rights of Blacks and the authority of Republican politicians and their allies.

Even after the Klan was effectively suppressed in the 1870s, political violence against Black voters, office holders, and jurors was endemic to the Southern United States and much of the North. Groups such as the White League, the Red Shirts, and others used terrorism to intimidate voters and oust Black and Republican politicians and sheriffs.

Ultimately, most United States’ leaders were uncomfortable using their political and military power to defend Black people from White southerners and eventually withdrew from enforcing the Constitution in the South by the end of the 1870s. It would not be until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that the US government, goaded by hundreds of thousand of activists risking their lives, would again attempt to use its power to secure Americans’ constitutional rights in the South, and to dismantle the systems of segregation throughout the North and the West.

Sources:

The Enforcement Act of 1870- Blackpast

The Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871- US Senate

Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871- National Constitution Center

Documenting Reconstruction Violence- Equal Justice Initiative